UNTOUCHABLE: THE RISE AND FALL OF HARVEY WEINSTEIN REVIEW

2nd Sep, 2019

UNTOUCHABLE: THE RISE AND FALL OF HARVEY WEINSTEIN REVIEW

2nd Sep, 2019

The Guardian by Lucy Mangan

UNTOUCHABLE: THE RISE AND FALL OF HARVEY WEINSTEIN REVIEW – FILMS LIKE THIS CHANGE THE WORLD

5 / 5 stars

What’s it like to be cajoled, threatened and blackmailed by a sexual predator who has power, history and society on his side?

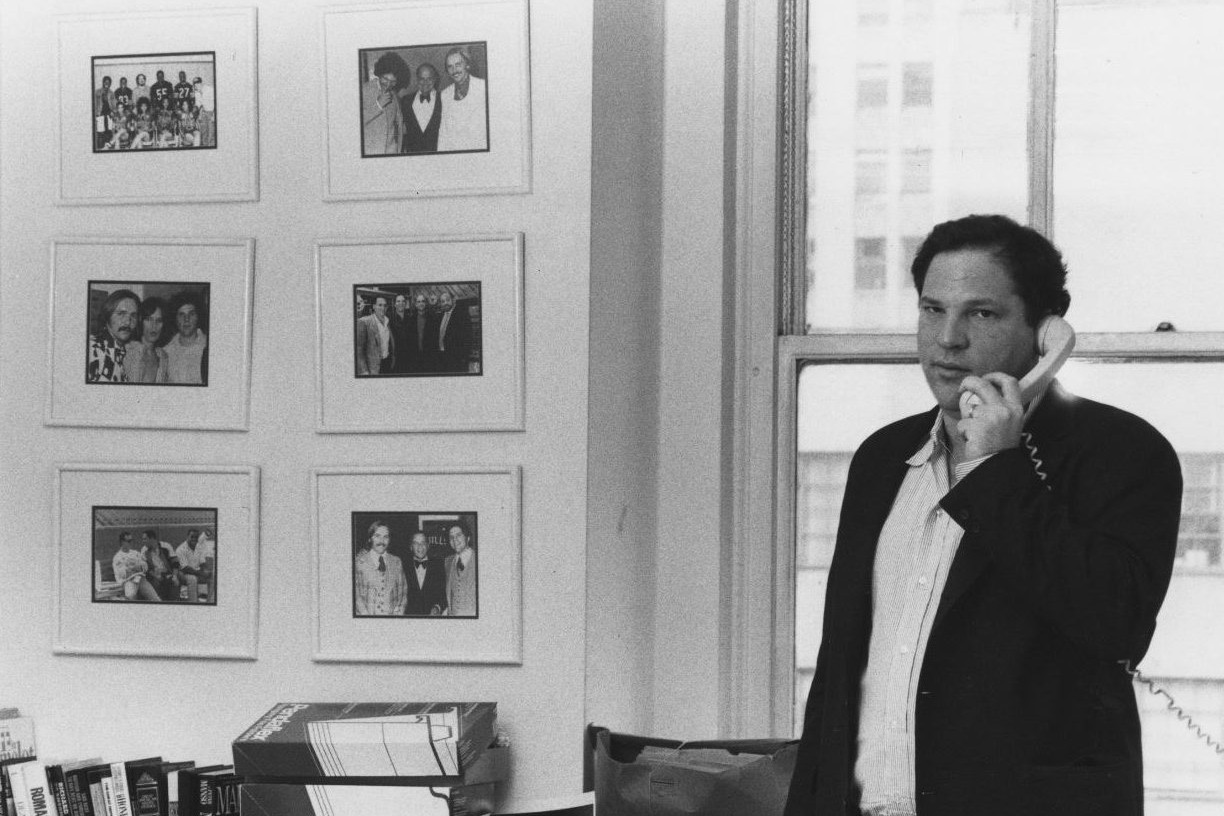

Untouchable: The Rise and Fall of Harvey Weinstein (BBC Two), directed by Ursula MacFarlane, is a film of halting testimonies, long pauses, lips pressed tightly together and eyes filling with tears. Of women struggling to articulate what they have left unsaid sometimes for decades, and what has gone unsaid by our sex – en masse – throughout history, until now.

You probably know the basic story – by osmosis if nothing else – so heavily was the media mogul’s eventual fall covered when the weight of evidence finally became too much for a man of even his resources to withstand. It shows the uniformity of the women’s responses to suddenly finding themselves in terrifying situations

MacFarlane tells the story well. She gives due recognition to the journalists, especially Megan Twohey and Jodi Kantor, who broke the story in the New York Times, and Ronan Farrow’s gathering of 13 witness accounts in the New Yorker after painstaking investigations. But, like Dream Hampton’s Surviving R Kelly, Untouchable prioritises the victims’ stories (regardless of their personal celebrity or lack thereof – here “names” such as Rosanna Arquette simply slip in next to those without public profiles) and fills in the perpetrator’s to explain his relative power or position at the time. As with the R Kelly film – thought to have been instrumental in the R’n’B star’s latest arrest on federal sex trafficking charges – a pattern of predatory behaviour emerges, painted stroke by painful stroke by those who found themselves first charmed and cajoled by one version of Weinstein, then confronted with a very different one behind closed doors.

Whether we should be profoundly glad, deeply sad or simply exhausted to be living in a time where “examination of the lives of serial sexual predators unmasked after years of hiding in plain sight” is on the verge of becoming a recognised TV genre, let alone one taking up the slack left by uninterested police and legislative forces, I leave to you to decide. But we are where we are. Which is, waiting to see who gets their Jeffrey Epstein production off the blocks first.

Beyond a specific modus operandi – Weinstein’s involved hotel suites, towelling robes, forcible massages, volcanic rage and threats such as: “Do you really want to make an enemy of me for five minutes of your time?” – as an insight into one man’s apparent prelude to rape or assault (Weinstein denies all claims), such documentaries render a more valuable service in demonstrating, relentlessly and unavoidably, two things.

The first is how perfectly our world is built for predators to function. Of Weinstein’s staff who admit they knew something – something – was happening, a common refrain is that they assumed “some sort of agreement” had been reached between the would-be actors and the mogul. If you live in a society that already believes in the casting couch, because the concept of young women as more-or-less sexual resources to be exploited is so embedded in the psyche, half your work – to normalise your predilections, to secure complicity – is done. With the likes of the gossip columnist AJ Benza out there – “You put a light on the porch,” he says of Weinstein’s power, “you’re gonna get a lot of moths” – the world is yours to do with as you will.

The second, perhaps even more valuable, service it renders is to show the uniformity of the women’s responses to suddenly finding themselves in terrifying situations, and how far they deviate from “common sense” or “natural” expectations (words defined almost entirely by men, who have least need of them). They don’t fight. They compute their chances against a much taller, heavier opponent (“He’s huge, you know,” says Hope d’Amore, who worked for him in the early days and says she was assaulted in 1978) and they go still. “The freeze thing kicks in,” says the actor Caitlin Delaney. “You just want it to be over.” They maximise their chances of survival (“I felt leaving would be worse,” says actor Erika Rosenbaum, when she saw a smashed and bloody toilet seat in his bathroom) and try and leave in other ways instead. Actor Paz de la Huerta remembers “hovering over my body” as, she says, Weinstein raped her. “I definitely went somewhere else,” says Delaney. Rosenbaum remembers hoping that if she kept still enough she would somehow disappear.

Almost every woman watching will understand. Some men will, too. If these films add to their number, maybe we can begin to change the world.