‘UNTOUCHABLE’: FILM REVIEW | SUNDANCE 2019

26th Jan, 2019

‘UNTOUCHABLE’: FILM REVIEW | SUNDANCE 2019

26th Jan, 2019

The Hollywood Reporter by Leslie Felperin

The rise and fall of Harvey Weinstein is recounted by some of the women he allegedly abused as well as colleagues who knew him and still feel the guilt in Ursula Macfarlane’s documentary.We’re living in a time when the news eco-system is as densely crammed with tales of the perfidy of rich, powerful men as a square kilometer of Amazonian rainforest is packed with endangered life forms. Consequently, the shocking (albeit not entirely surprising within the industry) revelations about the predatory habits of Harvey Weinstein, recounted in director Ursula Macfarlane’s scrupulous documentary Untouchable, almost feel like the fading echoes of an ancient supernova, one that exploded way back in the distant mists of October, 2017.

But the reverberations from Weinstein’s alleged misdeeds can still be felt today through the evolving collective story of the #MeToo movement, as ever more public figures are pulled into the undertow, while older accusations are made new again with fresh revelations. See, for example, the recent allegations published this month about Bryan Singer, while in Sundance, where Untouchable debuted, TV series Leaving Neverland also screened for the first time, offering four hours’ worth of detail about Michael Jackson’s alleged sexual abuse of the young boys he groomed as “friends.” Moreover, the Weinstein story is about to heat up again given that his trial, for charges of rape and two counts of predatory sexual assault, is scheduled to start in May.

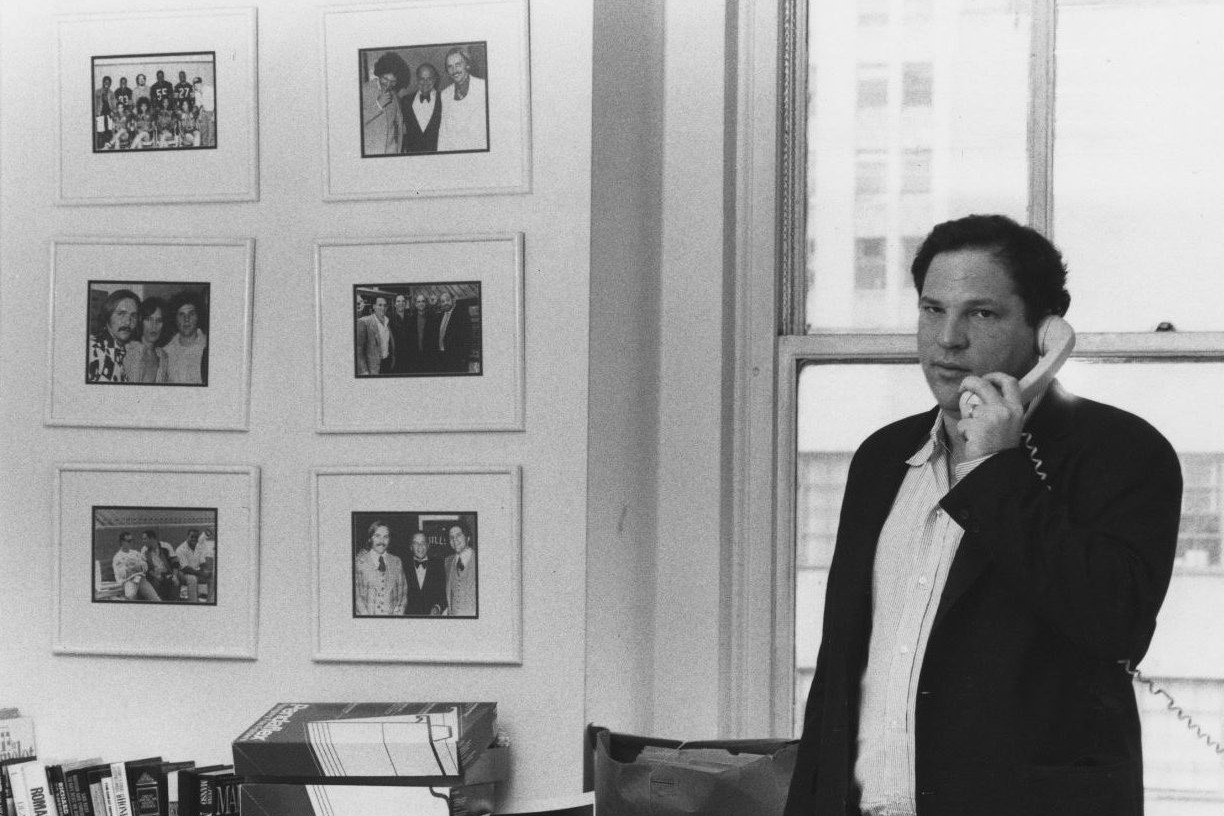

Told with clarity, respect and empathy, and not just for the women on whom Weinstein preyed, Macfarlane’s film offers a timely and fascinating overview of his story, one that’s almost emblematic of the pathology of serial sexual abusers. Former employees and colleagues from his earliest days in Buffalo as a music promoter and on through the early years of Miramax, the film company he founded with his brother Bob, recollect with justifiable admiration his passion for film, his good taste in material and his gift for marketing and making hits. Some are even willing to go so far as to admit that he could be undeniably charming and charismatic, but as one former executive notes, the flipside of that “genius” was a gluttonous appetite for power and pleasure.

Sensation seekers should be warned that there aren’t really any fresh allegations aired here, and Untouchable allocates just as much screen time to interviews with “non-famous” women Weinstein allegedly importuned or assaulted as it does to the likes of actors Rosanna Arquette and Paz de la Huerta, both interviewed here. But there is something extraordinary and immediate about these women’s narratives of what happened to them, told with honesty but evident and intense pain. Arguably the most devastating moment is when the camera holds patiently on one-time Weinstein employee Hope D’Amore for many seconds of screen time as she struggles to find the words to describe a sexual assault by Weinstein that happened in 1978. (“I didn’t scratch his eyes out, but I did say no and tried to push him away,” she says with painful frankness.) It’s in scenes like this that the film vibrates with an emotional richness and cathartic charge that the written journalistic word would struggle to match.

Macfarlane spends just about the right amount of time prodding at Harvey’s psychology in order to propel the story, but the real meat of the movie is its engagement with those who came into his orbit and became as damaged as they were enriched by the exposure. Those include not just the women he allegedly attacked or pressured or threatened, but to an extent also the people he worked with who sort of knew but sort of didn’t want to know, or even outright knew and chose to keep on working with him. Jack Lechner, at one time head of development at Miramax, John Schmidt, formerly a Miramax CFO, and Mark Gill, president of Miramax Los Angeles, all speak eloquently about their feelings of shame and survivor’s guilt. Kathy Declesis, at one time Bob Weinstein’s assistant, can at least hold her head high when recounting how she quit after reading a letter from a lawyer detailing the rape of another employee, but how many knew of similar assaults and chose to do nothing? The diffuse contagion of guilt is in some ways the real subject of this film.

After detailing how she was allegedly raped by Weinstein, Paz de La Huerta talks haltingly about how she felt a need to assert her sexuality even more on screen and in photo sessions as a kind of self-therapy, attempting to take back control of her own body and sensuality after the violation. As a kind of aesthetic correlative of this, each of the interviewees here are beautifully made up and flatteringly lit by cinematographers Patrick Smith and Neil Harvey. The glossy production values given them a sort of visual armor, and serve to remind us how Weinstein pathologically coveted beauty, perhaps because he was so uncomfortable in his own skin.

In the interests of full disclosure, The Hollywood Reporter’s editor-at-large Kim Masters is one of several journalists interviewed here about her dealings with Weinstein over the years. Her contributions are insightful, as is the one from prominent writer Rebecca Traister and her one-time boyfriend Andrew Goldman, who recount, with some tension-dissipating and welcome hilarity, a bizarre evening where they were verbally and physically assaulted by Weinstein, but still managed to record him boasting profanely about how he was the virtual sheriff of New York — and, as the title notes, untouchable.

Venue: Sundance Film Festival (Documentary Premieres)Production: A Lightbox Production in association with BBC, Samuel Marshall Films, Embankment FilmsDirector: Ursula MacfarlaneProducers: Simon Chinn, Jonathan Chinn, Poppy DixonExecutive producers:Charles Dorfman, David Gilbery, Tom McDonald, Simon Young,Hugo Grumbar, Tim HaslamCo-producer: Vanessa TovellDirectors of photography: Patrick Smith, Neil HarveyEditor: Andy R. WorboysMusic: Annie NikitinSales: Embankment Films98 minutes