MCQUEEN: FILM REVIEW | PROVINCETOWN 2018

22nd Jun, 2018

MCQUEEN: FILM REVIEW | PROVINCETOWN 2018

22nd Jun, 2018

The Hollywood Reporter by David Rooney

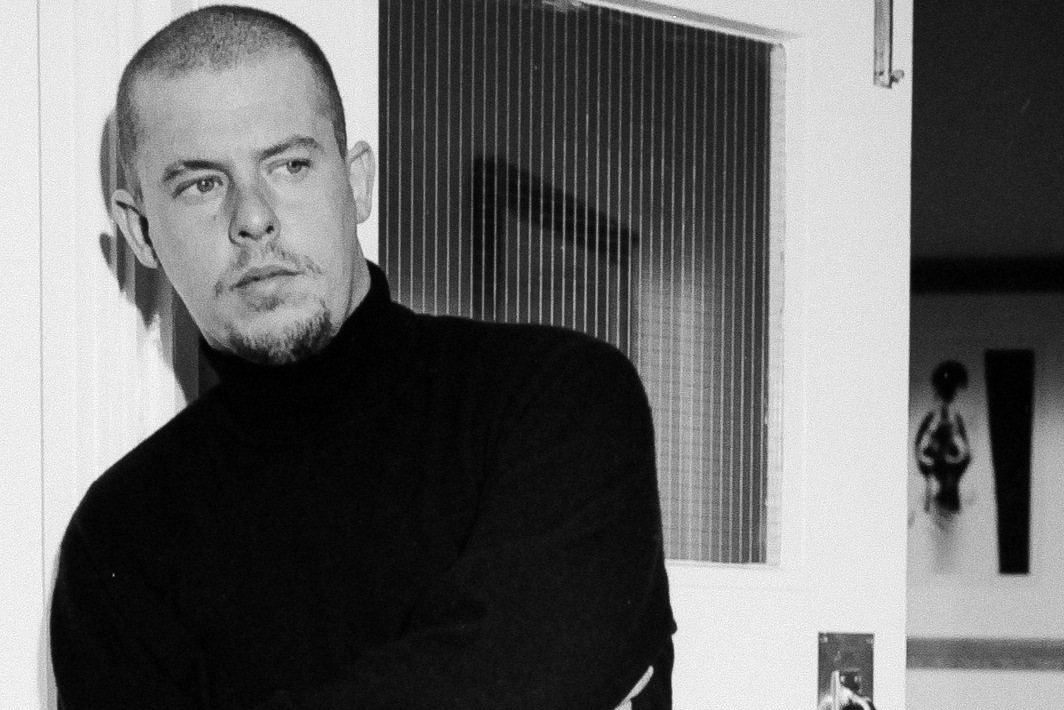

The classic narrative of a troubled creative genius flying too high too fast acquires emotional depth to match its visual splendors in Ian Bonhote and Peter Ettedgui’s sensory documentary portrait of Alexander McQueen.

It will be no news to the million-plus people who saw the stunning posthumous Alexander McQueen retrospective Savage Beauty — which broke attendance records in 2011 at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art and then four years later at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum — that the designer’s runway shows were transfixing happenings that fused theater, cinema, art, history and fantasy in visions both ethereally beautiful and darkly disturbing.

A similar career survey forms the spine of McQueen, a ravishing portrait by filmmakers Ian Bonhote and Peter Ettedgui that amplifies over and over again the late designer’s stated aim with his shows — to provoke emotion, whether it be repulsion or exhilaration. At the same time, the film illuminates the deeply affecting personal details of a life that blazed with dangerous intensity only to be snuffed out by tragedy. In the crowded field of fashion docs, this one stands tall.

McQueen’s success as both tribute and investigation is due in large part to the filmmakers’ skill at balancing sensitivity with bold creative flourishes. They trace the rags-to-riches story of the chubby high school dropout from working-class East London, Lee Alexander McQueen, with genuine empathy, via the words of the man himself and candid interviews with several of the people closest to the late designer. But they also look behind the freaky catwalk theater that made him such a celebrated enfant terrible, portraying an artist with a relentless work ethic, an intuitive gift for tailoring, a joyful spirit of collaboration and a punky irreverence toward the rules of the fashion establishment.

It’s that combination of impeccable skill with fearless imagination and unpretentious attitude that made McQueen such an enduring influence, while the relevance of other discoveries of the 1990s “Cool Britannia” wave has waned.

The movie is presented in five chapters, titled “tapes” after a jokey interview project with friends, and punctuated by the skull motif that remains the iconic symbol of McQueen’s design house today. In gorgeous digital animation sequences accompanied by the lush sounds of a Michael Nyman score full of surging pomp and drama, the skull is continually deconstructed and reshaped — oozing blood, armored with liquid metal and jewels, streaming with tendrils of tartan fabric like a Scottish Medusa, crawling with butterflies or decomposing as wilting petals fall from its gold-encrusted cavities.

Morbid yet beautiful, these powerful images of death might seem rather literal for a film whose subject took his own life at age 40 in 2010. But instead they serve as evocative visual binding, haunting echoes of the psychological demons manifested in such unorthodox ways in McQueen’s shows. Much has been written since his death about the tortured, self-destructive artist consumed by drug addiction and a dark side he couldn’t outrun. But Bonhote and Ettedgui mostly eschew those clichés in favor of a more intimate exploration.

Considerable time and attention is devoted to McQueen’s friendship with maverick fashion influencer Isabella Blow, who purchased his entire graduation collection when he was at St. Martin’s School of Art and became a major booster of his brand. (She convinced him to drop Lee and go with Alexander because it sounded “posher.”) But the first comment heard in the documentary, from designer John McKitterick, is quite telling: “Lots of people claim they discovered him, but Lee discovered himself.”

From his earliest days in the rag trade — learning bespoke tailoring and pattern cutting as a Saville Row apprentice, or running off to Milan with nothing but chutzpah and scoring a job assisting Romeo Gigli, who recalls with amusement that McQueen wrote “Fuck you, Romeo” in the lining of a troublesome jacket — it’s clear that McQueen was uncommonly driven.

Bobby Hillson, founder of the MA in fashion design at St. Martin’s and a fabulous character herself, describes McQueen as ugly and uneducated yet she was sufficiently swayed by his passion to invite him to take her course, for which his aunt paid the tuition. By all accounts a “nightmare student,” he was convinced he knew more than the tutors, but his prodigious talent was self-evident from his very first show in 1992, “Jack the Ripper Stalks His Victims.” That collection, cobbled together out of cheap materials and favors from friends, also established the element of violence present in much of his work.

In one memorable anecdote from those early years before notoriety had translated to commercial success, we learn that Richard Avedon wanted to photograph Sharon Stone in a cellophane McQueen dress, putting the designer and the garment on a Concorde flight to New York. Meanwhile, McQueen recalls that he barely had enough money for food, scooping up and eating a McDonald’s meal after he accidentally dropped it on the floor.

The doc shows McQueen’s hunger to make money, but not as a means to distance himself from his roots. Even when he was frolicking around Hilles, the stately Gloucestershire home of Blow — a world of cultivated eccentricity brought drolly to life in interviews with her foppish widower, Detmar Blow — he maintained strong links to home.

His mother Joyce encouraged his pursuit of a career in fashion and was always present at his shows, while his aunt made sandwiches and sausage rolls to feed the models. Some of the most moving interviews are with his sister Janet and her son Gary, who worked for McQueen as a textile designer. Janet was 15 years Lee’s senior; witnessing her almost strangled by the husband who sexually abused him as a child had a profoundly damaging effect on him that would last into adulthood. The documentary posits that wealth, drugs and the physical and mental demands of designing up to 14 collections a year at his most productive peak combined to make him increasingly depressed and isolated.

While there are key absences among the talking heads, notably longtime stylist Katy England, there’s a wealth of professional observations and tender personal recollections from former collaborators and friends like hairstylist Mira Chai-Hyde and designer Sebastian Pons. But the biographical thread of the film would be nothing without the breathtaking footage of the shows themselves, which thankfully, were video-documented to an extensive degree despite predating the Instagram age.

In addition to “Jack the Ripper,” these include “The Highland Rape,” a controversial, headline-making early show in which McQueen drew charges of misogyny by sending models down the runway in the tattered clothing of assault victims. The show was McQueen basically trashing the idea of romantic silk tartans used by Vivienne Westwood by tracing his own family ancestry back to Scottish warrior clans. In “It’s a Jungle Out There,” he put models in latex fetishwear and animalistic hair and makeup; and in his debut haute couture collection for Givenchy, the Jason and the Argonauts-inspired “Search for the Golden Fleece,” he crowned Naomi Campbell with massive golden antlers. The avant-garde theatricality of these spectacles remains thrilling.

The film suggests that transitional period with Givenchy was the beginning of McQueen losing himself and becoming a persona, a process later intensified when he transformed his body with liposuction. On one hand he refused to play the diva, as was expected of Parisian master designers, instead insisting on eating in the basement staff cafeteria with the workers. On the other, he resented the superior treatment given to John Galliano at Dior, the jewel of the LMVH group, with four times his budget.

Still, this is one of the film’s most entertaining sections, conveying the rebel spirit of a scrappy British lad and his tight-knit crew being set loose on fashion’s old guard. There’s keen observation also of how the initial shock of the seasoned atelier staff at Givenchy gave way to admiration for McQueen’s artistry.

Equal importance is given to the distancing of Isabella Blow, who felt betrayed and abandoned when McQueen’s star ascended and he declined to take her along for the ride in Paris. This now seems like a foreshadowing of the deterioration of his working relationships as McQueen became more paranoiac and volatile.

Tape Four is devoted to “VOSS,” the brilliant 2001 show staged in a giant cube whose mirrored outer walls forced the fashion press to contemplate themselves during the long wait for the deliberately late start. The lights then came up on an asylum within, the models with bandaged heads shooting unnerving glances beyond the glass, some of them tearing at their garments. (One actually snaps the brittle shards of cuttlefish that make up an extraordinary dress.)

While McQueen’s stated provocation was to accuse the fashion media of breeding insanity, the unsettling images now seem to say as much about his own tormented mind. The show climaxed with a macabre tableau based on American photographer Joel-Peter Witkin’s “Sanitarium,” with the opaque glass walls of a box at the center of the room crashing down to reveal a voluptuous naked woman in a gas mask, surrounded by moths. That model, Michelle Olley, delivers perhaps the film’s funniest comment: “Fat birds and moths, isn’t that just fashion’s worst nightmare?”

The final tape is “Plato’s Atlantis,” the 2009 Paris show in which McQueen introduced the famous armadillo shoe, with cameras on tracks like dinosaurs, stalking the models. This was a further evolution of a technological coup de theatre McQueen had staged 10 years earlier, putting the model Shalom Harlow on a turntable while two industrial robots scrutinize her somewhat menacingly before dousing her white dress with spray paint from snake-like nozzles. Showstoppers like that one; the half-naked woman in an open kimono battling wind and snow in a glass corridor from 2003; or the dream-like Kate Moss hologram from 2006, are expertly contextualized in a film that mirrors McQueen’s runway shows by blitzing us with visuals so dazzling they’re almost overwhelming.

The concluding section also covers “La Dame Bleue,” the 2008 show McQueen staged in collaboration with famed milliner Philip Treacy as a tribute to Blow, who had helped put both designers on the map. Bonhote and Ettedgui are oddly coy about the horrific method of Blow’s suicide the year before (she drank weedkiller). But they draw a poignant line from her death to the loss of McQueen’s beloved mother in 2010, and his own suicide a week later, by hanging, on the eve of her funeral.

McQueen is a haunting story of extravagant talent, restless creative energy and inescapable private sorrow, made with exquisite craftsmanship worthy of its subject. While a narrative biopic has been in development for years, this excellent documentary delivers an eye-popping, emotionally wrenching experience that paints a fully dimensional portrait of a complex artist.