MCQUEEN CAPTURES THE HIGH EMOTION AND CREATIVE BRILLIANCE OF THE LATE FASHION DESIGNER

27th Apr, 2018

MCQUEEN CAPTURES THE HIGH EMOTION AND CREATIVE BRILLIANCE OF THE LATE FASHION DESIGNER

27th Apr, 2018

Vulture

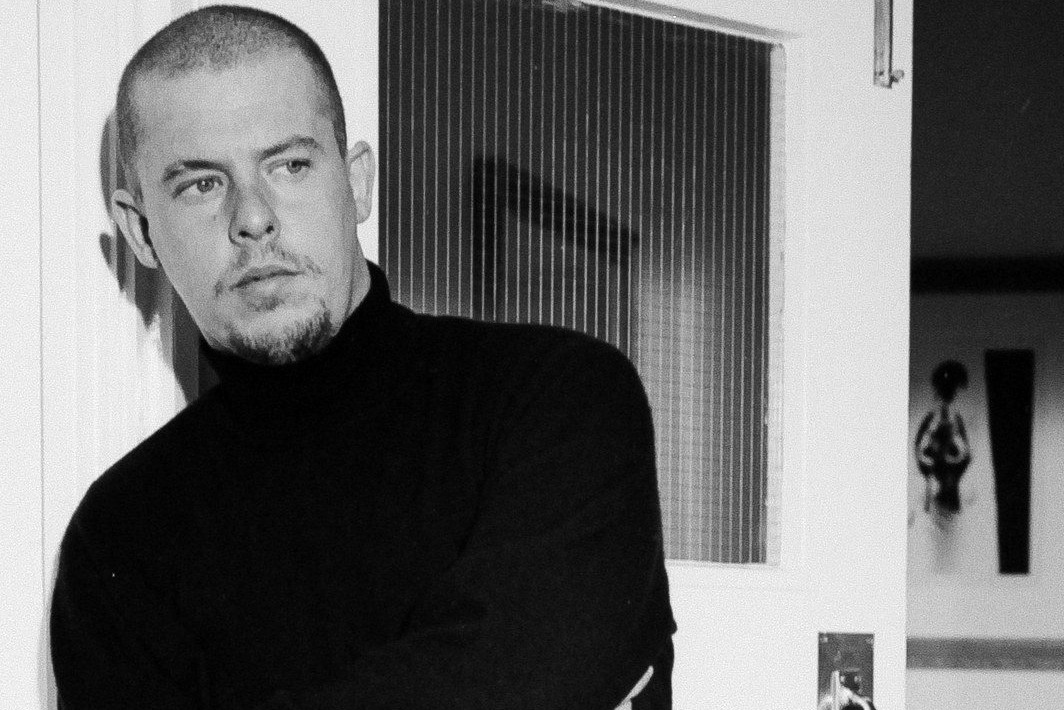

The skull motif, launched over a decade ago and seen now on countless knockoff scarves around the world, might be the most lasting imprint of the late British designer Alexander McQueen. Given his suicide in 2010, it’s a legacy that risks feeling both uncomfortably on the nose and overly simplistic, especially for a designer whose explosive, frequently morbid imagination took so many other less literal forms. But in the hands of directors Ian Bonhôte and Peter Ettedgui, it’s an endlessly pliable canvas, from the first frame of McQueen and throughout, in evocatively animated chapter markers. Bonhôte and Ettedgui find new dimensions in the skull’s contours, covering it in creeping gold filigree or reflecting the misty Scottish highlands off of it, letting it be both chilling or gorgeous depending on the context of their subject’s tumultuous life. It’s a brilliant, evocative touch that demonstrates early on how deep the film is willing to go in its appreciation.

McQueen (known to friends and family by his given name, Lee) rose to fame in the bubbling London of the 1990s, and by the turn of the millennium, became recognized as one of the most audacious, technically inventive contemporary fashion designers of his day, if not in the field’s modern history. Given these superlatives, McQueen could have been a perfectly respectable career retrospective. His body of work, even tragically cut short as it was, is abundant material, enough to fuel blockbuster shows at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Victoria and Albert Museum. But film and video might be the only medium that can capture the excitement of what McQueen was doing at the apex of his career, because it was so inherently cinematic. McQueen could have simply presented his best creative moments — the scandalous 1995 Highland Rape show; his ethereal, inhuman final presentation in 2009 where the iconic Armadillo shoe was birthed — and it would have contained more emotion and drama than most Sundance narrative features.

But Bonhôte and Ettedgui are blessed with intimate, candid interviews with many of the people who worked closest with McQueen, as well as archival interviews with his late muse and booster Isabella Blow and his beloved mother Joyce. (The designer’s suicide occurred the night before her funeral.) This is also, luckily, an artist whose friends and co-workers were dutifully capturing much of the journey on their shaky camcorders. The shows are still the centerpieces of the film, but they take on new dimension as narrated by those who knew the designer best. His older sister sees her abusive relationship with her ex-husband in the staggering wreckage of the Highland Rape (a show that was decried as misogynistic at the time and still to this day). His friends who watched his body and personal style change as he entered the high-pressure upper ranks of the fashion world see a kind subversive confrontation in the unforgettable Voss show of 2001, which turned the runway into a two-way mirrored insane asylum with a voluptuous, moth-ridden succubus as its final reveal. Thanks to a beautifully lush, moody score by Michael Nyman and great sound editing, even a fan who has pored over these archives obsessively will see them in a new light.

What McQueen reminds those obsessives and laypeople alike is that fashion is an incredibly emotional art form, and McQueen’s work was some of the most moving there was or ever will be. His shows were more like works of modern dance or theater than commercial exhibitions, in which the only choreography was the incredibly heavy, deceptively expressive act of walking. (In 2003, he sent a model down a suspended glass corridor, literally throwing herself against a torrent of wind and snow in nothing but a thick brocade robe and goggles; the sight of it alone is enough to bring tears to one’s eyes, let alone the devastating context in which it’s placed in the documentary.) Yes, his creativity fueled a commercially successful brand that is still in operation to this day. But it also injected an entire industry with possibility and inspiration, and was cathartic like a great film or pop song, the operatic awe of it all accessible to those who will never so much as touch one of his haute couture creations. Bonhôte and Ettedgui make it even more accessible, earnestly and convincingly making the argument for fashion as not just art, but great art.