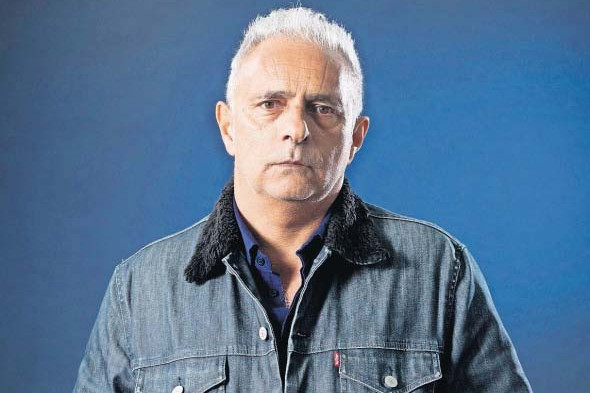

Hanif Kureishi: ‘I feel I could die at any moment’

16th Sep, 2024

Hanif Kureishi: ‘I feel I could die at any moment’

16th Sep, 2024

The Times

Hanif Kureishi: ‘I feel I could die at any moment’

The story of the author’s lifechanging accident is revealed in an intimate and darkly funny new film.

By Ed Potton

It was Boxing Day 2022 and Hanif Kureishi was in Rome, a the flat of his Italian girlfriend, Isabella D’Amico. “I was drinking a beer, smoking a joint, watching the football,” the writer of The Buddha of Suburbia and My Beautiful Laundrette says in a documentary for the BBC’s In My Own Words series. Seconds later, everything went fuzzy and I landed on my head”. The impact of the fall smashed nerves in his spinal cord and he woke up on the floor in a pool of blood. “I couldn’t feel my body. I saw my arms moving about but I didn’t know what they were, I thought they were sea creatures.”

“I was done for, my life was ruined. It was kind of over at that moment,” Kureishi says in the film. “I thought I was going to die.” He didn’t die but almost two years later he is still largely paralysed and confined to a wheelchair. The 69-year-old lives at home in Shepherds Bush, west London, where he is reliant on D’Amici and a team of carers to feed, wash and dress him.

Although he can no longer type, he can dictate. “The writing hasn’t stopped,” he says in the film. “It keeps you alive.” Like his friend Salman Rushdie, who was the victim of a horrific knife attack four months before Kureishi’s fall, he has “written things that I would never have written”. He is a regular tweeter and blogger, and Shattered, a memoir about the accident and its aftermath, is published next month. Kureishi is one of the most important British writers of the past half century. In the Eighties and Nineties he produced a stream of novels (the Whitbread-winning The Buddha of Suburbia, Intimacy), screenplays (the Oscar-nominated My Beautiful Laundrette, Sammy and Rosie Get Laid) and plays (Outskirts, Borderline) that were sexy, multicultural, political and intoxicatingly irreverent. “He had a, I hate to use the word, progressive voice but it wasn’t hysterical — you know, ‘I’m right and you’re wrong,’” says Nigel Williams, the writer and filmmaker who directed the documentary. “It was ironic, very English.” Born and raised in Bromley, southeast London, the son of a Pakistani father from a wealthy family and a white, lower-middle-class English mother, Kureishi is refreshingly at ease with his heritage.

“It creates difficulties for other people, really, being mixed race,” he says in the film. “It never bothered me because I knew where I belonged.” Williams met Kureishi in the early Eighties at Riverside Studios in London, where one of his early plays was being put on. They hit it off straight away. “If you like another writer’s work you tend to like him or her,” Williams says. “And if you don’t, you don’t. We became friendly, and then I said to Alan Yentob, ‘We should do a film about this guy.’” Yentob, later the controller of BBC2, was at the time the editor of the BBC’s Arena strand, for which Williams duly made a documentary on Kureishi in 1981. The two have been mates ever since and Williams was one of the first to his bedside in London after the accident.

It made him realise how many famous friends Kureishi has. “You met half of London there — Stephen Frears [who directed My Beautiful Laundrette] was amazing.” On another visit Williams bumped into the fashion designer Paul Smith. Among those who have written blurbs for Kureishi’s new book are Rushdie, Zadie Smith and the theatre director Richard Eyre.

Rushdie may feel he owes Kureishi because he had been hugely supportive after Iran issued a fatwa against him in 1989. Interviewed on TV shortly after the news broke, Kureishi said, “I feel deeply ashamed to have a Muslim name and come from a Muslim background.” “That was such a brave thing at a time when people were really nervous about it,” Williams says. “He tells it like it is. He’s got strong views and he’s very straightforward.”

Kureishi talks in the film about Rushdie visiting his home while in hiding and his bodyguards “looking in the shower to make sure there were no terrorists there”. One of them left his gun under the sofa. Kureishi returned it to him, saying, “Mate, you left your shooter behind.” He has clearly lost none of his wit. “Everyone says I’m the same irritating person I was before,” Kureishi says.

“Except that I’m entirely dependent on other people.” Mentally, he is “as sharp as ever”, Williams says. “If something like that happened to me I’d have turned to jelly, which he did not. He was always able to make a joke. Once, as I walked out of the ward, he said, ‘Enjoy your legs, Nige.’ That’s very Hanif.”

In one piece of footage from the hospital in Rome, Kureishi sucks on an ice lolly, which he compares to “the greatest blowjob you can ever imagine”. When they watch that clip in the film, he tells Williams, “I look pretty rough there. I’m like Usain Bolt now compared to what I was like then.”

Up to a point. He has more movement in his hands now, enough to control his electric wheelchair, but needs help writing — we see his twin sons, Carlo and Sachin, sitting at the keyboard and suggesting edits. Kureishi has three sons, all in their twenties: Carlo and Sachin, from his relationship with Tracey Scoffield, a film producer; and Kier, with Monique Proudlove, a charity worker.

Leaving Scoffield inspired his 1998 novel, Intimacy, which became a film starring Mark Rylance. “A lot of people got annoyed because the main character [in Intimacy] seems selfish and a bit of a twat,” Kureishi tells Williams, aware that some thought the same about him. “I was a much more dissolute father than my own father — I walked out on my own family quite soon after creating them,” he says, adding with typical candour, “I really enjoyed having kids but at the same time it really ruins your life.” Scars have healed since then. “It’s quite amazing that Hanif, Tracey and Isabella all get on, an object lesson in tolerance,” Williams says. Kureishi’s sons, meanwhile, have a healthily impertinent relationship with their father. “They’re never afraid to confront him,” Williams says, remembering a lunch with Roger Michell, who directed the TV adaptation of The Buddha of Suburbia. When a film came up in conversation, Kureishi said, “Great movie,” and one of his sons replied, “You only watched half of it, Dad.”

That kind of levity must be important because there are many moments of darkness. “I feel I could die at any moment,” Kureishi says at one point. When he had his accident it wasn’t his past that flashed before his eyes but his lost future: “Places I wanted to go, conversations I wanted to have.” There is also, however, a renewed appreciation for a rollicking life. “I wanted to be a writer, to have sex with lots of women, have a family and friends, and to love other people and be loved by them in a reciprocal way,” Kureishi says. “So I would say I’ve achieved quite a lot of that.”

In My Own Words: Hanif Kureishi is on BBC1 and iPlayer tonight at 10.40pm