BREATHE FILM REVIEW – LONDON FILM FESTIVAL BY THE INDEPENDENT

4th Oct, 2017

BREATHE FILM REVIEW – LONDON FILM FESTIVAL BY THE INDEPENDENT

4th Oct, 2017

The Independent by Geoffrey Macnab

SURPRISINGLY ENTERTAINING VIEWING IN ITS OWN VERY BRITISH FASHION

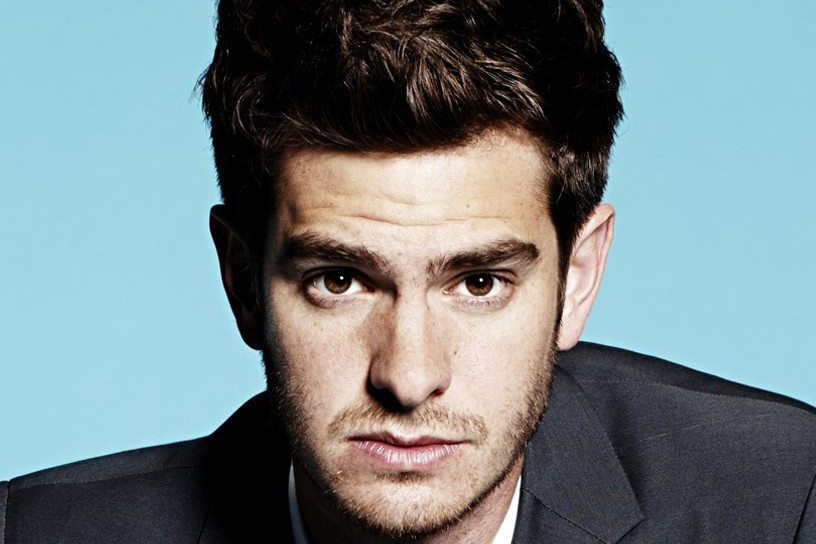

ANDREW GARFIELD STARS AS AN UPPER-CLASS ENGLISHMAN WITH POLIO WHO IS GIVEN WEEKS TO LIVE IN THE DIRECTORIAL DEBUT OF ACTOR ANDY SERKIS

The premise is daunting. Breathe (which opened the London Film Festival) is a biopic telling the story of Robin Cavendish, a dashing upper-class Englishman struck down with polio, paralysed from the neck below and given weeks to live. It’s a grim starting point but the film (the directorial debut of actor Andy Serkis) makes rousing and surprisingly entertaining viewing in its own very British fashion.

We are used to seeing Andrew Garfield (who plays Cavendish) scaling buildings in Spider-Man movies or dashing heroically across the battlefield in Hacksaw Ridge. Here, once the illness strikes, he’s like a rag doll that can’t move at all. He has a tube attached to his throat which is connected to a vacuum-like machine that does his breathing for him. Garfield still manages to give an energetic and upbeat performance, smiling joyously and, once he has recovered the powers of speech, showing off his dry wit and enormous joie de vivre.

Breathe is bound to be compared to The Theory Of Everything, in which Stephen Hawking has motor neurone disease but still manages to enjoy a lively family life and enormous academic success. Cavendish is different from Hawking. He’s a cricket and tennis-playing outdoors man who drives a sports car and, before his illness, seems incapable of staying still.

The film is as much about Cavendish’s wife Diana (Claire Foy on leave from The Crown) as it about Cavendish himself. Without her, he would have died very quickly. “She’s a famous heartbreaker” we are told when she first appears, looking glamorous in a prim 1950s-floral-dress-wearing way, at a cricket match in which Cavendish is playing. Her character here resembles one of those selfless heroines that actresses like Phyllis Calvert used to play in old Ealing movies. She is always understated. “It’s a bit of a bugger. I am never going to be able to have fun again,” is how she tells her husband the happy news that she is pregnant. They’re the perfect couple – and then he contracts polio. Everyone else’s assumption is that he will die quickly in the hospital and she will move on with her own life. Instead, she battles against the bureaucrats and disdainful surgeons to be allowed to bring him home. Once she has him there, she acts as his nurse as well as his wife. If his ventilator becomes unplugged, he will die within minutes. When his lungs bleed, she is the one who will have to clean up the mess.

Parts of Breathe are very predictable. We know that he is going to prove the medical experts wrong and that he will find a way of enjoying himself in spite of his debilitating illness. Cavendish is surrounded by friends, wine lovers, bon viveurs and inventors among them. There seems to be a travelling party that accompanies him wherever he goes. With Diana to help, a specially customised wheelchair and a car adapted for his use, he is soon travelling both at home and abroad.

William Nicholson’s screenplay doesn’t dwell on some of the more humdrum elements of its subject’s life. For example, Diana makes a great fuss about not having much money and not being able to afford a nanny but that doesn’t stop her buying a country house. We are never sure who is paying for the jaunts to Spain or the lavish parties. The role of class in 1950s and 1960s Britain is ignored. The focus here is generally on the most colourful moments in Cavendish’s life. Not much attention is paid to the enormous stretches of what must have been bed-bound boredom. Cavendish exists in a bubble with his aristocratic friends, among them his endearing twin brothers-in-law (both played by Tom Hollander in subtly different waistcoats and ties so we can tell them apart). Although he tries hard to help fellow polio sufferers, we are always aware that he is in a far more privileged position than they are.

One of the likeable aspects of Breathe is its lack of sanctimoniousness. Whether Cavendish is stuck in Spain with a broken ventilator or attending a disability conference in Germany, there is always a sense of mischief and adventure about his experiences. He is never portrayed as simply the victim.

In the early Nairobi-based scenes, Cavendish tells a story about Mau Mau warriors in British captivity who were able to will themselves to die. When the polio strikes, he does the opposite and wills himself to live. Cavendish is told he will be lucky to survive two weeks but the years rush by. We leap from 1965 to 1970 (an excuse for a flower power-style party at the country house) and then onto the 1980s. An increasingly episodic film begins to seem like a cinema version of a family album. The storytelling risks becoming a bit too glib and too cheerful and in downplaying the severity of its protagonist’s condition. On the upside, there’s an energy and optimism here which belie the grim subject matter and Serkis knows just how to tweak our heart strings when it comes to the final reel.